AIUS LOCUTIUS

I am an embalmer of a crumbling friendship. I have endured the fetid slime of gratuitous vilification, yet I rise above the Race of Reptiles and overlook the affront. The trilling of the thrush’s throat could not have been more explicit. The rank indecency of David Schoffman’s recent attack on me is a grim reminder of his covetous misery. Yet, as I sit here in my luxurious garden, swilled by the perfume of Peruvian daffodils and sweet alyssums, I can only offer my forgiveness and compassion.

In a recent interview, broadcast on Canal Plus, David Schoffman offered some unjustifiable and calumnious characterizations that betray the covenant of our friendship. I include an excerpt below:

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

UCCELLI

It’s been well documented that David Schoffman has an avid fascination for birds. In a 1995 profile in Prague’s Nový Prostor, Schoffman spoke at length about the maniacal mewl of the Silesian Eagle Owl, a bird whose enveloping wingspan and conspicuously ornate facial disc are legendary throughout Central Europe. In the same interview David described the six months he spent in Sri Lanka studying the Spotted Dove and the Ashy-Headed Laughing Thrush. “I drew constantly,” he said, “trying to depict the rapture of flight and the showers of light as they played off of the brilliant infinitude of brown and gray. It was a painter’s paradise and “Chanticleers and Columbiformes,” my series of hand-colored monotypes would have been inconceivable without this seminal experience.”

What David failed to mention in the article was the string of damp beds, the pangs of unembroidered poverty, the galling feuds and oppressive doubts that characterized that six-month sojourn. I remember receiving letters full of odd hallucinations, paranoiac fantasies and erotic misadventures. Names like Mosby the Sailor, Silas The Street-Prophet, Mufti Sam and Lalima filled his rambling missives that read more like novels and irate manifestoes. To this day I am unsure how much of what he wrote was true and how much was fantasy.

That was many years ago, and David has been leading a productively sedate, even boring existence for some time. I am happy that Prolix Press has recently re-issued “Chanticleers and Columbiformes” in limited edition. It is a sobering reminder that the wages of disquiet, traded by the gifted hand, can yield precious monuments to our more noble selves.

It’s been well documented that David Schoffman has an avid fascination for birds. In a 1995 profile in Prague’s Nový Prostor, Schoffman spoke at length about the maniacal mewl of the Silesian Eagle Owl, a bird whose enveloping wingspan and conspicuously ornate facial disc are legendary throughout Central Europe. In the same interview David described the six months he spent in Sri Lanka studying the Spotted Dove and the Ashy-Headed Laughing Thrush. “I drew constantly,” he said, “trying to depict the rapture of flight and the showers of light as they played off of the brilliant infinitude of brown and gray. It was a painter’s paradise and “Chanticleers and Columbiformes,” my series of hand-colored monotypes would have been inconceivable without this seminal experience.”

What David failed to mention in the article was the string of damp beds, the pangs of unembroidered poverty, the galling feuds and oppressive doubts that characterized that six-month sojourn. I remember receiving letters full of odd hallucinations, paranoiac fantasies and erotic misadventures. Names like Mosby the Sailor, Silas The Street-Prophet, Mufti Sam and Lalima filled his rambling missives that read more like novels and irate manifestoes. To this day I am unsure how much of what he wrote was true and how much was fantasy.

That was many years ago, and David has been leading a productively sedate, even boring existence for some time. I am happy that Prolix Press has recently re-issued “Chanticleers and Columbiformes” in limited edition. It is a sobering reminder that the wages of disquiet, traded by the gifted hand, can yield precious monuments to our more noble selves.

Monday, March 10, 2008

THE GUESTS OF ABRAHAM

Like many immigrants to the United States, David Schoffman experienced fully both the exuberance of opportunity and the diligence of pain. His early struggles with idiomatic English were often comic. Overhearing how an acquaintance had “quit cold turkey,” he wondered for years about the hazards of the nation’s ubiquitous deli counters. When an embattled critic described his first one-man show as “the trifling bathos of a party-hearty paper-pusher,” he was completely flummoxed, and remains so to this day.

Like Unamuno’s Quixote, David found his true fatherland in exile. Though never comfortable with America’s Levitic distrust of the senses, he is fully at ease in the country’s ritual embrace of pragmatic, can-do independence. He realized early that the culture was a thriving polyphony of personal re-invention. Together with lawyers and clergymen, schemers, rouges, recluses and visionaries stoked the hot flame of liberty’s torch. It’s a nation of cardsharps and Schoffman fell in love with it as only one not native to it can.

His rise to the upper echelons of artistic Elysium was an unparalleled act of creative deception. Claiming to be the illegitimate son of the eccentric Marchesa Luisa Casati, he inveigled an audience with Jefferson MacNeice, the former curator of painting and drawing at the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge. Passing off some drab watercolors of his “mother” that he hastily painted on the train from New York, he arranged an exhibition devoted to the beddabled Casati legacy. For a fifty percent split on the proceeds I agreed to write the catalog essay and filled it with mad claims, cross-referenced footnotes and a phony blurb from a feeble Andre Derain.

The rest is (recent art) history.

Like many immigrants to the United States, David Schoffman experienced fully both the exuberance of opportunity and the diligence of pain. His early struggles with idiomatic English were often comic. Overhearing how an acquaintance had “quit cold turkey,” he wondered for years about the hazards of the nation’s ubiquitous deli counters. When an embattled critic described his first one-man show as “the trifling bathos of a party-hearty paper-pusher,” he was completely flummoxed, and remains so to this day.

Like Unamuno’s Quixote, David found his true fatherland in exile. Though never comfortable with America’s Levitic distrust of the senses, he is fully at ease in the country’s ritual embrace of pragmatic, can-do independence. He realized early that the culture was a thriving polyphony of personal re-invention. Together with lawyers and clergymen, schemers, rouges, recluses and visionaries stoked the hot flame of liberty’s torch. It’s a nation of cardsharps and Schoffman fell in love with it as only one not native to it can.

His rise to the upper echelons of artistic Elysium was an unparalleled act of creative deception. Claiming to be the illegitimate son of the eccentric Marchesa Luisa Casati, he inveigled an audience with Jefferson MacNeice, the former curator of painting and drawing at the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge. Passing off some drab watercolors of his “mother” that he hastily painted on the train from New York, he arranged an exhibition devoted to the beddabled Casati legacy. For a fifty percent split on the proceeds I agreed to write the catalog essay and filled it with mad claims, cross-referenced footnotes and a phony blurb from a feeble Andre Derain.

The rest is (recent art) history.

Friday, February 29, 2008

SHIFTING MUSES

David Schoffman is losing his eyesight. Like Degas, Borges and The Green Lantern, David’s macular disinterphicus is slowly shepherding him into the gloomy pitch. “The Body Is His Book,” his ongoing series of dizzyingly transcendent paintings may well be his last. As he descends into the black-tar of blindness, he continues to work with the unforfeited optimism of a dreamer. As the starless shroud begins to muffle his wildness, the urgency of his vision becomes more pressing. His newest works show no signs of despair and as he lifts the flag upon the mast of his artistic mission, he pulses forward with ambition and ever increasing complexity.

“The invention of painting belongs to the gods,” he wrote to me last week, quoting Philostratus, “and the gods are reclaiming their gift.” I am ashamed to say that a part of me rejoiced, as the only artist worthy of exciting my nasty competitive impulses will soon be receding into inactivity. This ugly urge is further testament to the titanic nature of David’s genius.

Eyes maimed by blindness may only husband other talents, greater gifts, for an intellect as supple as Schoffman’s will not be scuttled by mere infirmity.

He has already shown signs of a tectonic shift. An accomplished amateur musician, David has begun composing a song-cycle based on Hesiod’s Works and Days. The first piece, “What’s All the Fuss About the Slayer of Argus” is a catchy, somewhat sentimental ditty that may very well catch fire in today’s extremely eclectic music scene.

David Schoffman is losing his eyesight. Like Degas, Borges and The Green Lantern, David’s macular disinterphicus is slowly shepherding him into the gloomy pitch. “The Body Is His Book,” his ongoing series of dizzyingly transcendent paintings may well be his last. As he descends into the black-tar of blindness, he continues to work with the unforfeited optimism of a dreamer. As the starless shroud begins to muffle his wildness, the urgency of his vision becomes more pressing. His newest works show no signs of despair and as he lifts the flag upon the mast of his artistic mission, he pulses forward with ambition and ever increasing complexity.

“The invention of painting belongs to the gods,” he wrote to me last week, quoting Philostratus, “and the gods are reclaiming their gift.” I am ashamed to say that a part of me rejoiced, as the only artist worthy of exciting my nasty competitive impulses will soon be receding into inactivity. This ugly urge is further testament to the titanic nature of David’s genius.

Eyes maimed by blindness may only husband other talents, greater gifts, for an intellect as supple as Schoffman’s will not be scuttled by mere infirmity.

He has already shown signs of a tectonic shift. An accomplished amateur musician, David has begun composing a song-cycle based on Hesiod’s Works and Days. The first piece, “What’s All the Fuss About the Slayer of Argus” is a catchy, somewhat sentimental ditty that may very well catch fire in today’s extremely eclectic music scene.

Friday, February 15, 2008

AUTHENTICITY

It’s time to acknowledge the debt, owed by David Schoffman, to two illustrious though unsung artists of the recent past. Schoffman’s evasions are understandable. His fears that a nod toward his predecessors may taint his eminence are well grounded. Accolades accrued through misconception will ultimately sully a well-earned legacy so I have taken it upon myself to illuminate upon David’s artistic antecedents.

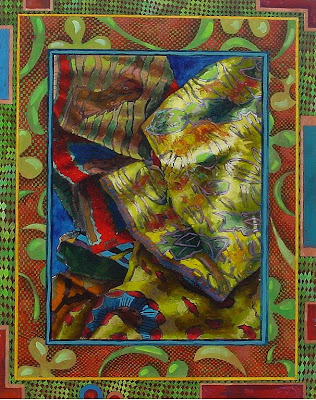

Medussa Moratti knew no pangs of constraint nor did he harbor the fitful discontent of his peers. He was a man comfortable in his own skin and at home in his own studio. Though virtually unknown, Moratti’s work was extremely influential among the Parisian avant-garde of the 1970’s. His perplexing treatise, “Toward The Unsung,” unlocked a convulsive wave of ribald experimentation. That his reputation was eclipsed by his acolytes is one of the many injustices he suffered as a visionary. Below is “Fervid Geysers Rise,” a piece that proved instrumental in Schoffman’s development.

The Canadian Bedouin Noah Clrec was slightly better known. His gauzy paintings depicting wreaths of vapor, buoyantly gladdened by gravitational ambivalence were well received at the time though largely unrecognized today. Schoffman was among a small circle of frothy young artists who attended his regular lectures at The Free School on Boulevard Arago. Clerc often referred to his theory of “bolted withdrawal,” a form of sensual self-denial that ultimately leads to original invention. He argued that through willed isolation, artists could free themselves of what he called “the commanding hiss of history” and create un-mined categories and modes of expression. An early untitled Clerc is reproduced below.

Schoffman will undoubtedly deny the shadow this casts upon his reputation. He prefers the naked myth that defines him as the stony hedge of ingenuity.

The naked feet of an appropriator are rarely kissed.

It’s time to acknowledge the debt, owed by David Schoffman, to two illustrious though unsung artists of the recent past. Schoffman’s evasions are understandable. His fears that a nod toward his predecessors may taint his eminence are well grounded. Accolades accrued through misconception will ultimately sully a well-earned legacy so I have taken it upon myself to illuminate upon David’s artistic antecedents.

Medussa Moratti knew no pangs of constraint nor did he harbor the fitful discontent of his peers. He was a man comfortable in his own skin and at home in his own studio. Though virtually unknown, Moratti’s work was extremely influential among the Parisian avant-garde of the 1970’s. His perplexing treatise, “Toward The Unsung,” unlocked a convulsive wave of ribald experimentation. That his reputation was eclipsed by his acolytes is one of the many injustices he suffered as a visionary. Below is “Fervid Geysers Rise,” a piece that proved instrumental in Schoffman’s development.

The Canadian Bedouin Noah Clrec was slightly better known. His gauzy paintings depicting wreaths of vapor, buoyantly gladdened by gravitational ambivalence were well received at the time though largely unrecognized today. Schoffman was among a small circle of frothy young artists who attended his regular lectures at The Free School on Boulevard Arago. Clerc often referred to his theory of “bolted withdrawal,” a form of sensual self-denial that ultimately leads to original invention. He argued that through willed isolation, artists could free themselves of what he called “the commanding hiss of history” and create un-mined categories and modes of expression. An early untitled Clerc is reproduced below.

Schoffman will undoubtedly deny the shadow this casts upon his reputation. He prefers the naked myth that defines him as the stony hedge of ingenuity.

The naked feet of an appropriator are rarely kissed.

Thursday, February 07, 2008

FAUST

I am very fond of David Schoffman. And though there is no balm to be found in such sentiments between men, there are times when I think that my affection for him borders on love. But it is a backbreaking exertion, toil of excruciating industry, a labor that rewards with only the wages of humiliation and grief.

His character is the small voice of weights and measures. He is a striver who sees human interaction as trade. Long ago he renounced his faith in art in favor of the puny stanchions of acclaim. He would barter his Atman for even the slightest material advantage. He would betray a colleague, double-cross a friend, denounce his kin in order to till the clay of his career.

The first-fruits of his labor were quite impressive. As a young man, fresh out of art school, he caught the gleam of Patricia Paschal, chief curator for contemporary art at the auction-house Betise Françoise. She recklessly sponsored his assent by planting bogus bidders to swell the estimates on his under-incubated paintings. The product of David’s vigorous coital enterprise ended badly for Patty - her marriage to film director Sandor Van Hoght was shattered, her credibility as an art dealer, destroyed - but quite well for him. It was a succès de scandale that sent his prices soaring.

Ever since, Schoffman’s story has been one of professional bouquets and personal iniquity. He has banished grace to garner eminence and he has been triumphant.

I am his only remaining friend.

I am very fond of David Schoffman. And though there is no balm to be found in such sentiments between men, there are times when I think that my affection for him borders on love. But it is a backbreaking exertion, toil of excruciating industry, a labor that rewards with only the wages of humiliation and grief.

His character is the small voice of weights and measures. He is a striver who sees human interaction as trade. Long ago he renounced his faith in art in favor of the puny stanchions of acclaim. He would barter his Atman for even the slightest material advantage. He would betray a colleague, double-cross a friend, denounce his kin in order to till the clay of his career.

The first-fruits of his labor were quite impressive. As a young man, fresh out of art school, he caught the gleam of Patricia Paschal, chief curator for contemporary art at the auction-house Betise Françoise. She recklessly sponsored his assent by planting bogus bidders to swell the estimates on his under-incubated paintings. The product of David’s vigorous coital enterprise ended badly for Patty - her marriage to film director Sandor Van Hoght was shattered, her credibility as an art dealer, destroyed - but quite well for him. It was a succès de scandale that sent his prices soaring.

Ever since, Schoffman’s story has been one of professional bouquets and personal iniquity. He has banished grace to garner eminence and he has been triumphant.

I am his only remaining friend.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

MARS THREE SHEETS TO THE WIND

At the recent 14th Annual Conference of Poets and Scholars in Chicago, I attended an interesting symposium entitled “Jehovah’s Mooring: The Resurgence of Academic Drawing in the United States.” Among the speakers was Francois Clarel, the distinguished linguist from the Université de Cergy-Pontoise. From his privileged Val-d’Oise perch, the return of the largely discredited 19th century French pictorial aesthetic is a laughable matter. To Clarel, this is the sort of folly that makes Americans so adorable and so pitiable in French eyes.

Many attendees agreed and yet the smug nature of his assertions was rather insulting to his hosts. It was to the great credit of my friend, David Schoffman to have had the grace and presence of mind to speak on the subject with greater equanimity, unwavering dignity and sparkling erudition.

In brief, David’s argument is that the history of painting up until the mid-19th century is a story of a client-based economy. The dependence upon patrons and princes delayed the advent of “pure self-expression” till Baudelaire. Notable exceptions like Blake or Goya’s Quinta del Sordo notwithstanding, to greater or lesser degrees, the customer was always right. Perhaps the highpoint of craven subservience to the moneyed clientele was the 19th century French Academy.

Drawing, according to Schoffman, was always the exception. Renaissance and Baroque artists painted for their clients but drew for themselves and their workshop assistants. Drawing was almost never meant for public consumption and as such was always more speculative, fluid and personal. In effect, it was self-expression before this type of urging had a name.

The recent American fascination with 19th century drawing techniques such as “sight-sizing” is an unwitting retreat into creative subservience to the marketplace. The United States with its Puritanical undercurrents is the perfect breeding ground for this type of phenomenon. Distrustful of the senses and fascinated by quantifiable statistics, many of today’s revisionist artists are drawn to an aesthetic that serves simultaneously as a theology and an exam.

Schoffman’s speech received a prolonged standing ovation, a rarity among the jaded community of pointy-headed tenured know-it-alls. Later that evening at the reception hosted by the glamorous socialite Shania McBean, David, much to the astonishment of his collegues, kicked the shit out of the pompous professor Clarel.

Friday, January 18, 2008

LIVING LIKE BRUTES

Delivering a lecture at the Saur Center for Post-Graduate Studies attended mostly by young people working on their Masters degree in the visual arts, David Schoffman noted that the students in general, quoting Virginia Woolf, were “unhappy and rightly malignant.”

The dry, hot air of the auditorium held the faint odor of cabbage and not a few of the students lightly dozed during the forty-minute talk. The putative topic, as advertised in the department’s monthly brochure, was “The Delirium of William Blake,” but Schoffman, notorious for his impromptu digressions, wandered off into Dante’s depiction of Ulysses. “Considerate la vostra semenza,” Schoffman roared, stirring the somnolent and alarming the security guards who the week before had to quell a near riot after a bearded lecturer screamed something equally menacing in an equally foreign tongue.

Evoking Inferno’s 26th canto or any other canto for that matter among MFA students is typically seen as bad form. These newly minted artists do not want to be prodded into a messianic fervor by a middle-aged painter who still uses a palette knife. They want either densely packed hermetic aphorisms that include the word “conflate” or the word “disjunction” (or, preferably both), or they want practical marketing tips they can use the next time the dealers come marching through their cramped studios.

Speaking in Italian is also seen as bad form, as is French and Latin. Young artists today are linguistic nativists, preferring to communicate in the international language of mammon. Collectors, I was told rather bluntly by a professor of New Genre Studies at NYU, are uncomfortable around polymaths of any sort but are particularly put off by one with a ring in their nose. “By the time an art student reaches grad school, they are pretty well trained in keeping their erudition on the down low.”

So Schoffman, a man famously remote and inaccessible, was innocent of these niceties and stumbled, hat first, into a cauldron of cynicism. “Fatte non foste viver come bruti/ Ma per seguir virtute e conoscenza,” he continued, completing the tercet. “Artists,” he went on, “remember your origins! It is not gain, but enlightenment that you are after!”

I’m not certain whether David actually managed to finish his sentence, but the pie seemed to come out of nowhere. A group calling itself “Nuevos Destructores de Imagen” claimed responsibility and later circulated a manifesto around campus entitled “Against The Color Blue.”

Delivering a lecture at the Saur Center for Post-Graduate Studies attended mostly by young people working on their Masters degree in the visual arts, David Schoffman noted that the students in general, quoting Virginia Woolf, were “unhappy and rightly malignant.”

The dry, hot air of the auditorium held the faint odor of cabbage and not a few of the students lightly dozed during the forty-minute talk. The putative topic, as advertised in the department’s monthly brochure, was “The Delirium of William Blake,” but Schoffman, notorious for his impromptu digressions, wandered off into Dante’s depiction of Ulysses. “Considerate la vostra semenza,” Schoffman roared, stirring the somnolent and alarming the security guards who the week before had to quell a near riot after a bearded lecturer screamed something equally menacing in an equally foreign tongue.

Evoking Inferno’s 26th canto or any other canto for that matter among MFA students is typically seen as bad form. These newly minted artists do not want to be prodded into a messianic fervor by a middle-aged painter who still uses a palette knife. They want either densely packed hermetic aphorisms that include the word “conflate” or the word “disjunction” (or, preferably both), or they want practical marketing tips they can use the next time the dealers come marching through their cramped studios.

Speaking in Italian is also seen as bad form, as is French and Latin. Young artists today are linguistic nativists, preferring to communicate in the international language of mammon. Collectors, I was told rather bluntly by a professor of New Genre Studies at NYU, are uncomfortable around polymaths of any sort but are particularly put off by one with a ring in their nose. “By the time an art student reaches grad school, they are pretty well trained in keeping their erudition on the down low.”

So Schoffman, a man famously remote and inaccessible, was innocent of these niceties and stumbled, hat first, into a cauldron of cynicism. “Fatte non foste viver come bruti/ Ma per seguir virtute e conoscenza,” he continued, completing the tercet. “Artists,” he went on, “remember your origins! It is not gain, but enlightenment that you are after!”

I’m not certain whether David actually managed to finish his sentence, but the pie seemed to come out of nowhere. A group calling itself “Nuevos Destructores de Imagen” claimed responsibility and later circulated a manifesto around campus entitled “Against The Color Blue.”

Friday, January 11, 2008

FLAMES ALONG THE GULLET

“Don’t misuse the gift.”

Those were Bruno Mazzotta’s last words before seeing David Schoffman off from the port of Fortaleza. Mazzotta, Brazil’s beloved poet of grief (second only to the unapproachable Prato Mauro), had just finished his long awaited volume of sonnets, “Crags and Escarpments,” and was working with Schoffman on the illuminated edition. Together with David’s lapidary illustrations, the book went on to win the coveted “Borda Dourada Prize” as 2001’s best literary collaboration of text and image.

Their creative alliance, paraphrasing the famous Portuguese proverb, was like a mosquito on an unharvested grape.

A few years earlier, Schoffman was in Sao Paulo exhibiting his flawed series of lithographs “Flames From The Eighth Crevasse” at Martin da Fonseca’s now defunct Museum of Erotic Art. At a dinner party at Guadencio’s, the trendy bistro known for spiking its Cajuzhho with marinated flaxseed, the two artists had a notorious public row.

It seems that Mazzotta’s wife Fabiola - a woman whose passion for Cachaca rum had instigated not a few South American scandals in the past – began toasting her Caipirinha’s to what she graphically described as Schoffman’s thewy sexual stamina. The poet was understandably infuriated and with great ceremony, challenged the painter to a duel.

To avoid more grievous injury, Schoffman promptly clocked Mazzotta squarely on the jaw, ending the party and sending the injured poet to the emergency room. Later, through lawyers, they agreed to settle all claims and damages by Schoffman’s agreement to work gratis on the sonnet project.

“Crags And Escarpments” sold 1,400,000 copies and was translated into 23 languages. Schoffman, who toiled in front of his easel creating 31 unique paintings for each of the 31 poems, did not receive a single cruzado for his efforts. To this day, the ownership of the actual pictures is being contested in court.

“Don’t misuse the gift.”

Those were Bruno Mazzotta’s last words before seeing David Schoffman off from the port of Fortaleza. Mazzotta, Brazil’s beloved poet of grief (second only to the unapproachable Prato Mauro), had just finished his long awaited volume of sonnets, “Crags and Escarpments,” and was working with Schoffman on the illuminated edition. Together with David’s lapidary illustrations, the book went on to win the coveted “Borda Dourada Prize” as 2001’s best literary collaboration of text and image.

Their creative alliance, paraphrasing the famous Portuguese proverb, was like a mosquito on an unharvested grape.

A few years earlier, Schoffman was in Sao Paulo exhibiting his flawed series of lithographs “Flames From The Eighth Crevasse” at Martin da Fonseca’s now defunct Museum of Erotic Art. At a dinner party at Guadencio’s, the trendy bistro known for spiking its Cajuzhho with marinated flaxseed, the two artists had a notorious public row.

It seems that Mazzotta’s wife Fabiola - a woman whose passion for Cachaca rum had instigated not a few South American scandals in the past – began toasting her Caipirinha’s to what she graphically described as Schoffman’s thewy sexual stamina. The poet was understandably infuriated and with great ceremony, challenged the painter to a duel.

To avoid more grievous injury, Schoffman promptly clocked Mazzotta squarely on the jaw, ending the party and sending the injured poet to the emergency room. Later, through lawyers, they agreed to settle all claims and damages by Schoffman’s agreement to work gratis on the sonnet project.

“Crags And Escarpments” sold 1,400,000 copies and was translated into 23 languages. Schoffman, who toiled in front of his easel creating 31 unique paintings for each of the 31 poems, did not receive a single cruzado for his efforts. To this day, the ownership of the actual pictures is being contested in court.

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

THE KNIFE THAT CUT BOTH WAYS

On BBC’s “Bright Lights” recently, David Schoffman was asked by Philip Tenson, the program’s obsequious host, how the city of Los Angeles had affected his work. As a native New Yorker, David is asked that question often and each time he modifies his answer. Perhaps reckoning that his British audience would not take umbrage, David delivered, what in my mind was his most thoughtful response.

“Los Angeles,” he began, “is a city, staggering in its ugliness. It ranks up there with Riyadh, Chernobyl and Tucson. A day does not go by where I am not struck by the city’s total disregard of urban design. It is a hodge-podge of competing affronts. It is a mass of crushing aesthetic neglect. Braids of cumbersome billboards clumsily project into the sky like lopped fingers. Pedestrian-free boulevards sob with a constant stream of slow traffic. Priapic palm trees compete joylessly with the ubiquity of cement.

“An artist can’t help but thrive in such an environment. A place so estranged from beauty, so indifferent to its own toxic shadows is an oven of ferocious artistic resentment. Every act, every thought, every gesture by the artist is an act of rebellion and critique.

“It’s an emboldening atmosphere where every creation, however slight will be an improvement. So hostile is Los Angeles to the inner eye that even minor talents thrive there.”

“Bright Lights” is fortuitously broadcast immediately following Great Britain’s most popular half hour drama, “Porticoes and Transoms” and David’s interview attracted over half a million viewers. London’s Daily Mirror reported that following the show, travel agents experienced a wave of cancellations of trips to L.A. The most popular substitution was apparently Houston.

Monday, November 26, 2007

ALETHEIA

I’ve gotten many calls since my last posting comparing the work of my good friend David Schoffman with that of my departed colleague R. B. Kitaj. Not a few people questioned my bona fides, challenging my ability, as a lapsed Catholic, to evaluate the Jewish nature of these two giants’ work. Yishai Bar Laytzan even went so far as to call me a “teleological Torquemada” and that I should “stay the hell away from Jewish history.” The Reverend Deacon Stephen Tigglight, despite being a great patron of the arts in his native Wythenshawe , expressed his strong reservations regarding my juxtaposition of Schoffman’s oeuvre to the Pentateuch. He said I hadn’t managed to assimilate the critical aesthetic differences between works that “were divinely inspired and those divinely produced.”

I stand by my assessment.

Forgetting Kitaj for the moment, David Schoffman’s reliance on formal, non-objective, non-narrative pictorial strategies is fully consistent with uniquely Judaic apophatistic skepticism. His work demands a visualization that avoids materiality. As a lapsed Catholic I am uniquely qualified to draw the appropriate distinctions. Christian art is pedagogical, Jewish art is philosophical. Christian art is illustrative, Jewish art is abstract.

The forms in Schoffman’s work confirm the paradoxical Jewish predicament of depiction versus idolatry. His rejectionist stance toward descriptive imagery solves this dilemma through his elastic use of ambiguous symbolism. Drawing from the Kabbalah, Schoffman notates and validates with great originality multiple readings of his work. To stand in front of a Schoffman is like being blinded by the Shekhinah. One is present to a palpable presence yet one remains unsure as to the exact nature of what one is seeing.

If that’s not Jewish art, I don’t know what is.

I’ve gotten many calls since my last posting comparing the work of my good friend David Schoffman with that of my departed colleague R. B. Kitaj. Not a few people questioned my bona fides, challenging my ability, as a lapsed Catholic, to evaluate the Jewish nature of these two giants’ work. Yishai Bar Laytzan even went so far as to call me a “teleological Torquemada” and that I should “stay the hell away from Jewish history.” The Reverend Deacon Stephen Tigglight, despite being a great patron of the arts in his native Wythenshawe , expressed his strong reservations regarding my juxtaposition of Schoffman’s oeuvre to the Pentateuch. He said I hadn’t managed to assimilate the critical aesthetic differences between works that “were divinely inspired and those divinely produced.”

I stand by my assessment.

Forgetting Kitaj for the moment, David Schoffman’s reliance on formal, non-objective, non-narrative pictorial strategies is fully consistent with uniquely Judaic apophatistic skepticism. His work demands a visualization that avoids materiality. As a lapsed Catholic I am uniquely qualified to draw the appropriate distinctions. Christian art is pedagogical, Jewish art is philosophical. Christian art is illustrative, Jewish art is abstract.

The forms in Schoffman’s work confirm the paradoxical Jewish predicament of depiction versus idolatry. His rejectionist stance toward descriptive imagery solves this dilemma through his elastic use of ambiguous symbolism. Drawing from the Kabbalah, Schoffman notates and validates with great originality multiple readings of his work. To stand in front of a Schoffman is like being blinded by the Shekhinah. One is present to a palpable presence yet one remains unsure as to the exact nature of what one is seeing.

If that’s not Jewish art, I don’t know what is.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Closer To Jabès

With the death of R. B. Kitaj, the designation of preeminent contemporary Jewish painter has been bestowed upon David Schoffman. The contrasts in temperament and preoccupation of these two distinguished artists could not be more profound. Kitaj was the exquisite illustrator of themes and narratives germane to the modern, mostly secular Jewish world. His depictions of illustrious figures like Walter Benjamin, Kafka and Isaiah Berlin were indicative of his deep attachment and identification with these towering and uniquely Jewish intellectuals.

Schoffman, by contrast, eschews the literal while cultivating the riches of Jewish abstraction. Having grown up in a religious home in a religious neighborhood in Brooklyn, Schoffman’s complicated and lyrical reflections on the Jewish tradition draw as much from antiquity as they do from contemporary Jewish life. Like Schoenberg, Schoffman is obsessed with the relationship of Moses and Aaron and the uncanny nature of monotheism. The improbable attraction toward the invisible, the unempirical and the silent has been one of Schoffman’s salient themes.

Don’t look for stories or learned quotations in David’s work. In Kitaj you find an almost folkloric gloss of places and people, very much in the tradition of Chagall. Schoffman is more of a philosopher, an evoker rather than a declaimer, more in the spirit of Reinhardt, Rothko and Newman. However, unlike his predecessors, Schoffman has little patience with the severity of reductive self-denial. His is a world fully invested in the senses, a world rich in references to both the pious and the worldly, the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi, the Florentine and Venetian.

Kitaj, with his lovable pedantry will be missed. Schoffman is a great admirer of, if not the work, the man and the artist. Some may incline toward Kitaj’s lovely exemplification of ideas, his richly mannered citations and his beautifully bright colors. I for one prefer the complexity and ambiguity of Schoffman’s inventions. Like arcane Talmudic texts, what is expressed is secondary to the gorgeous inevitability of its logic.

Schoffman’s “The Body Is His Book” is not a rumination on the Pentateuch as much as it is the necessary addition of an important new chapter.

Friday, October 26, 2007

IDENTITY THEFT

I was amused the other day when I received the following email:

“Dear Mr. Malaspina,

What you write about David Schoffman is simply not true. Week after week I read your postings and each one is more fantastic than the next. You are spreading lies, weaving elaborate fables, prevaricating and exaggerating. You are a mythmaker, a calumnist, a delusional fantasist. You, with all your convoluted inventions are a literary nuisance.

I don’t even know where to begin. David Schoffman has never been to Morocco, has never exhibited his paintings in Laos, does not windsurf, does not speak Dutch, was not romantically involved with Carla Motta and her twin sister and has never spent a single solitary night in jail.

I have known Schoffman for over twenty years and I can assure you, he does not practice Sufism nor is he a vegetarian. In all the years I’ve known him he never once mentioned an epistolary relationship with Goddard, nor have I ever heard him discuss UFO’s.

The things you write about are spun from whole cloth. They are complete fabrications. As to your purpose, I have no idea.

The David Schoffman I know is a church going father of four who has spent the better part of his adult life practicing family law in Crown Point, Indiana. He hasn’t had a string of exotic mistresses nor does he associate with dancers and architects. True, he paints, but despite his impressive talent, he has never exhibited his work. (I own one of his oils, “Children Playing,” and it hangs proudly above our fireplace).

Mr. Malaspina, you do yourself and your readers a disservice with your weekly deceptions, regardless of how engaging and well written your posts are. In the future, before you publish another vignette, please send it to me for fact checking.

Sincerely yours,

Benny Toland”

Its funny to think that there is someone else with the name David Schoffman. I and so many others associate that name with the high-minded pursuit of aesthetic enchantment and delight. Odd to think that he could be confused with some guy in Indiana.

Anyway, Benny and anyone else out there who is puzzled about the identity of the man the intellectual community knows as “the” David Schoffman, I have posted a recent photo of him above.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

THE BREAD OF LIFE

Any pleasure that David Schoffman may take from life will only be that which manages to slip between the gallops of recollection. He lives with the murmur of futility. He paints in order to recover the ignorance that precedes memory.

When he studied with the writer, Allejo Abulafia, the ageless visionary and grand master of Ladino prose, he discovered the inevitability of sadness. Abulafia, who lived for many years among the flaming dunes of southern Morocco, saw life as something entombed in predestination. To him, our personal histories were merely grim rocks of insignificance. It was the artist’s bitter duty to impersonate meaning through creative introspection. The products of that puny introspection should be fit to rest upon Earth’s chest with a noble dignity. If it passes that test, then one has created Art.

Abulafia’s imagination, in his later years, was a dry river. Schoffman told me once that it was his mentor’s weakness for atonement that proved to be his undoing. “Be quick, before you are crucified by time,” were the last words Abulafia wrote in a journal entry titled “Conclusions.”

Monday, September 24, 2007

FATEFUL DETOURS

Experiencing conversation with David Schoffman is a geometrical progression of ever widening tangents and digressions. It’s a mind made transparent by the jags of association. A minor mention of a mosquito bite may lead to a lengthy discourse on Elias Canetti’s “The Agony of Flies.” The subject of sports may lead into Robert Musil’s passion for weightlifting. Musil inevitably leads into Bismarck, which always ends up with Henry Kissinger, the bombing of Cambodia and the overthrow of Allende.

Once, at a dinner party at the home of Maurice Vitel, the former French Ambassador to Luxembourg, the conversation veered toward the question of whether it was morally defensible to poison a flock of sparrows if they actively hindered the cultivation of one’s vineyard. A heated exchange ensued between those who militantly defended the rights of animals and those who militantly defended the rights of wine lovers. In a rare moment of détente while the debaters regrouped around aged cognac and Haitian cigars, Schoffman recounted the following anecdote:

“The failed writer, Boris Khrobkov, a distant relative of Isaac Babel, labored his entire life on an unfinished novel on the subject of the Huguenot exile. Living in the Soviet Union severely proscribed his ability to do the proper historical research and so he petitioned the cultural commissar of Vitebsk a well as the president of the writer’s union for permission to travel abroad. Despite his connection to Babel, his permission was granted for a one-week trip to Paris. His wife and two small children were, of course, required to stay behind.

“On his last day in Paris, where incidentally he did much drinking and very little research, he decided, on a whim, to visit the grave of Ingres at Père-Lachaise. It was late fall and sparrows had gathered in clusters around the islands of breadcrumbs left behind by the cemetery workers. Khrobkov, hung over and bitter about his impending return, grabbed a sparrow by the throat and crushed its skull like a walnut.

“Like any good Russian, he followed that arbitrary act of cruelty with an hysterical, inconsolable fit of weeping. At the very height of his shameless bleating, the great Cartier-Bresson walked by with his small field spaniel Molière. Always ready with his 35mm Lieca rangefinder, he snapped the now famous photograph 'Le Poét Pleurant.'

"Khrobkov returned to Moscow where he was accused of treason and was shot by a firing squad."

Experiencing conversation with David Schoffman is a geometrical progression of ever widening tangents and digressions. It’s a mind made transparent by the jags of association. A minor mention of a mosquito bite may lead to a lengthy discourse on Elias Canetti’s “The Agony of Flies.” The subject of sports may lead into Robert Musil’s passion for weightlifting. Musil inevitably leads into Bismarck, which always ends up with Henry Kissinger, the bombing of Cambodia and the overthrow of Allende.

Once, at a dinner party at the home of Maurice Vitel, the former French Ambassador to Luxembourg, the conversation veered toward the question of whether it was morally defensible to poison a flock of sparrows if they actively hindered the cultivation of one’s vineyard. A heated exchange ensued between those who militantly defended the rights of animals and those who militantly defended the rights of wine lovers. In a rare moment of détente while the debaters regrouped around aged cognac and Haitian cigars, Schoffman recounted the following anecdote:

“The failed writer, Boris Khrobkov, a distant relative of Isaac Babel, labored his entire life on an unfinished novel on the subject of the Huguenot exile. Living in the Soviet Union severely proscribed his ability to do the proper historical research and so he petitioned the cultural commissar of Vitebsk a well as the president of the writer’s union for permission to travel abroad. Despite his connection to Babel, his permission was granted for a one-week trip to Paris. His wife and two small children were, of course, required to stay behind.

“On his last day in Paris, where incidentally he did much drinking and very little research, he decided, on a whim, to visit the grave of Ingres at Père-Lachaise. It was late fall and sparrows had gathered in clusters around the islands of breadcrumbs left behind by the cemetery workers. Khrobkov, hung over and bitter about his impending return, grabbed a sparrow by the throat and crushed its skull like a walnut.

“Like any good Russian, he followed that arbitrary act of cruelty with an hysterical, inconsolable fit of weeping. At the very height of his shameless bleating, the great Cartier-Bresson walked by with his small field spaniel Molière. Always ready with his 35mm Lieca rangefinder, he snapped the now famous photograph 'Le Poét Pleurant.'

"Khrobkov returned to Moscow where he was accused of treason and was shot by a firing squad."

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

THE ANGELS NEVER TAKE FLIGHT

His eyes were like tongues inflamed. He had been up all night and his lids were a soggy crimson (had he been weeping?). His unsteady voice was like a dogcart over gravel. His hands were black with charcoal, his nails, early moons of soot.

He had been drawing.

It was Paris in the 70’s and David Schoffman was known as the hardest working, most unproductive painter among his peers. Sustained by faith, hope and Pernod his long apprenticeship was cheered only by the occasional trip to Rome. He was in the habit of working all night in an improvised studio a few blocks north of the Basilica of the Sacré Coeur. He was at war with what he called “the thunderous silence of Watteau and the silent thunder of Rothko.”

In those days, painting was more a confession then a profession. “Career” was a foreign phrase from the taxonomy of landlords and martinets. Painting was an obsession, a calling, a slow spiral into the perils self-knowledge. It took residence within the entrails of an artist with a fixed and incorruptible mastery. It withstood mockery and failure. It was the insatiable lover.

I am brought back to these memories as I vacation presently in a small villa in Kusadasi. Watching the wind sift through the palmettos, I hear the fishermen casting their nets into the quiet Aegean. Trawling for eel and octopus is also not a “career.”

We were right in those days. And we continue being right.

His eyes were like tongues inflamed. He had been up all night and his lids were a soggy crimson (had he been weeping?). His unsteady voice was like a dogcart over gravel. His hands were black with charcoal, his nails, early moons of soot.

He had been drawing.

It was Paris in the 70’s and David Schoffman was known as the hardest working, most unproductive painter among his peers. Sustained by faith, hope and Pernod his long apprenticeship was cheered only by the occasional trip to Rome. He was in the habit of working all night in an improvised studio a few blocks north of the Basilica of the Sacré Coeur. He was at war with what he called “the thunderous silence of Watteau and the silent thunder of Rothko.”

In those days, painting was more a confession then a profession. “Career” was a foreign phrase from the taxonomy of landlords and martinets. Painting was an obsession, a calling, a slow spiral into the perils self-knowledge. It took residence within the entrails of an artist with a fixed and incorruptible mastery. It withstood mockery and failure. It was the insatiable lover.

I am brought back to these memories as I vacation presently in a small villa in Kusadasi. Watching the wind sift through the palmettos, I hear the fishermen casting their nets into the quiet Aegean. Trawling for eel and octopus is also not a “career.”

We were right in those days. And we continue being right.

Friday, September 07, 2007

RESCUED BY ABSENCE

Just when David’s fragile tranquility was almost fully restored, he was forced, once again, to mingle among the footmen and princes of Los Angeles’ artworld. What cruel misfortune to have to endure the festive klatch of a “closing reception.” What horror feigning unmerry gladness among the chilly cognoscenti. I’m so grateful to be curled and wet within the comforting folds of Mother France.

I heard the reception was so crowded one had to wedge one’s way to the bar like a pickpocket in order to get a plastic cup of meek vinegary wine.

I heard that people hissed that Carpentier’s death was fortunate for sales, a crass, though accurate assessment. I’m told that my work was described as gratuitously concupiscent, a judgment I find typically American. Only Schoffman enjoyed unqualified acclaim, a magnet for flattery as if he were a rich and ailing uncle.

Though I left behind no gilded monuments, I was far from disgraced. I would be happy to return to Los Angeles and exhibit more work. Perhaps I will include palm trees in my next series.

Just when David’s fragile tranquility was almost fully restored, he was forced, once again, to mingle among the footmen and princes of Los Angeles’ artworld. What cruel misfortune to have to endure the festive klatch of a “closing reception.” What horror feigning unmerry gladness among the chilly cognoscenti. I’m so grateful to be curled and wet within the comforting folds of Mother France.

I heard the reception was so crowded one had to wedge one’s way to the bar like a pickpocket in order to get a plastic cup of meek vinegary wine.

I heard that people hissed that Carpentier’s death was fortunate for sales, a crass, though accurate assessment. I’m told that my work was described as gratuitously concupiscent, a judgment I find typically American. Only Schoffman enjoyed unqualified acclaim, a magnet for flattery as if he were a rich and ailing uncle.

Though I left behind no gilded monuments, I was far from disgraced. I would be happy to return to Los Angeles and exhibit more work. Perhaps I will include palm trees in my next series.

Saturday, September 01, 2007

CODA

Schoffman informs me that the unbuttoned denizens of Los Angeles need an extra week to see “Three Mendacious Minds”. Tranquilized by summer’s beneficence, armies of tardy sophisticates beseeched the gallery into extending the exhibition for several more days. Some have actually become zealots, returning to the show with the frequency of ardent lovers. I am heartened and grateful to these unappeasable enthusiasts and they are all welcome to visit me in Paris.

Cradled as he is by admirers, David Schoffman is nonetheless an unsatisfied man. When I saw him at the opening he appeared rain-beaten, almost bestial. He never gives throat to pleasure, as if the turbulence of his inner-life is too stirring. Contemplative to the point of desolate, some say he comes off as bruised and discourteous.

I’m told there will be a closing reception on Friday evening, September 7th. If you think David appears drowsy and disconsolate …. lui donnez une étreinte.

Tell him you were sent by Currado!

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

GRAVEN SILENCE

When David lived in Rome he had a small studio on Via della Reginella above an antiquarian book dealer named Castelvetro. Old Castelvetro would sit on a tattered folding chair in front of his shop immersed in the unraveling of knots plaiting long lengths of delicate twine. His gestures were slow and deliberate. Though void of all gaiety, he was profoundly unserious. With a glazier’s tact his feminine fingers would light ubiquitous cigarettes as he dispensed his primeval street wisdom. He spoke often of Italy and the Shoah, never with bitterness or anger but as if, through a verbal exertion, he could clarify a personal enigma.

One of his favorite books in his shop, a book he insisted he would never sell, was an early 19th century volume of the Talmudic tractate Sotah. He claimed it was the only remaining volume from the famous Leghorn Benedetti Edition. Schoffman was fascinated with this book.

Minimally ornamented, each page with its tiny marginalia of commentary, held for David a peculiar fascination. Castelvetro was very much taken with David’s passionate interest and allowed him to leaf through the surprisingly robust pages any time he felt like it.

David began doing drawings based on these pages and it is from these drawings came the idea for “The Body Is His Book: One-Hundred Paintings”.

Castelvetro passed away a few years ago and all my attempts to find out the fate of this beautiful book have come to naught. Perhaps it will turn up one day.

When David lived in Rome he had a small studio on Via della Reginella above an antiquarian book dealer named Castelvetro. Old Castelvetro would sit on a tattered folding chair in front of his shop immersed in the unraveling of knots plaiting long lengths of delicate twine. His gestures were slow and deliberate. Though void of all gaiety, he was profoundly unserious. With a glazier’s tact his feminine fingers would light ubiquitous cigarettes as he dispensed his primeval street wisdom. He spoke often of Italy and the Shoah, never with bitterness or anger but as if, through a verbal exertion, he could clarify a personal enigma.

One of his favorite books in his shop, a book he insisted he would never sell, was an early 19th century volume of the Talmudic tractate Sotah. He claimed it was the only remaining volume from the famous Leghorn Benedetti Edition. Schoffman was fascinated with this book.

Minimally ornamented, each page with its tiny marginalia of commentary, held for David a peculiar fascination. Castelvetro was very much taken with David’s passionate interest and allowed him to leaf through the surprisingly robust pages any time he felt like it.

David began doing drawings based on these pages and it is from these drawings came the idea for “The Body Is His Book: One-Hundred Paintings”.

Castelvetro passed away a few years ago and all my attempts to find out the fate of this beautiful book have come to naught. Perhaps it will turn up one day.

Thursday, August 23, 2007

THE OTHER LOS ANGELES

I am happy to be back in Paris, though I fully enjoyed my short sojourn in Los Angeles. Despite what many of my countrymen believe, southern California is not a tattered patch of inarticularity. Who are we to pass judgment? Are we so innocent as to satisfy our flawed self-image with a nostalgic look at Camus, Foucault and Aron? I have news for you. For every Derrida there are a thousand sausage-makers.

Schoffman surrounds himself with an exciting coterie of distinguished artists and intellectuals, all living under the balmy palms of L.A. The poet, Justin Spens has a silver-tipped wit and an astonishing reservoir of eccentric anecdotes. Sitric Hogan, the bird-boned dulcimerist, has the tenderest demeanor and a gift for celestial sight. The satanic imagination of Colette Nolan is thrilling evidence of the obsolescence of interdiction. J. Courtney Wain, despite the inelastic honorific is a multi-levered lover of all things Baltic and is as at home with the lilting lyrics of Juhan Liiv as she is with the minimalism of Lepo Sumera. With all this stimulating company it is amazing that Schoffman finds any time to paint.

But he is, as the sculptor Bernard Fann told me as he dropped me off at LAX, the consummate workaholic. “He inhales with a casual greed what Wallace Stevens called the ‘debris of life and mind’. He exhales paintings.”

I am happy to be back in Paris, though I fully enjoyed my short sojourn in Los Angeles. Despite what many of my countrymen believe, southern California is not a tattered patch of inarticularity. Who are we to pass judgment? Are we so innocent as to satisfy our flawed self-image with a nostalgic look at Camus, Foucault and Aron? I have news for you. For every Derrida there are a thousand sausage-makers.

Schoffman surrounds himself with an exciting coterie of distinguished artists and intellectuals, all living under the balmy palms of L.A. The poet, Justin Spens has a silver-tipped wit and an astonishing reservoir of eccentric anecdotes. Sitric Hogan, the bird-boned dulcimerist, has the tenderest demeanor and a gift for celestial sight. The satanic imagination of Colette Nolan is thrilling evidence of the obsolescence of interdiction. J. Courtney Wain, despite the inelastic honorific is a multi-levered lover of all things Baltic and is as at home with the lilting lyrics of Juhan Liiv as she is with the minimalism of Lepo Sumera. With all this stimulating company it is amazing that Schoffman finds any time to paint.

But he is, as the sculptor Bernard Fann told me as he dropped me off at LAX, the consummate workaholic. “He inhales with a casual greed what Wallace Stevens called the ‘debris of life and mind’. He exhales paintings.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)